Why is it important to look at indeterminacy today? Not long ago, this concept promised a widespread revolution in thought and practice. In the arts especially, indeterminacy was seen as holding a radically liberatory potential, promising to overturn long-standing norms not only in art, but across society. No hierarchies, from those of the fine arts to that of humanity over nature, seemed stable. Now, however, indeterminacy is the norm: as instability, uncertainty, or undecidability, from climate change to the digital systems’ perpetual optimisation and embroilment of habit. The open-endedness and unpredictability of indeterminacy has become a means for extending the reach of technologies of security and surveillance. We find ourselves asking how this disconnect between the liberatory potential of indeterminacy and indeterminacy as it appears today came about. Let me try and outline some features of this disconnect.

In twentieth-century science, indeterminacy was most prominently associated with the physicist Werner Heisenberg’s ‘uncertainty principle’. In its most radical interpretations, such as that of Heisenberg’s colleague Niels Bohr, what the uncertainty principle reveals is an indeterminacy at the level of reality itself. Recently, the philosopher Karen Barad has helped us see the consequences of Bohr’s theories, showing, for example, how indeterminacy means that subject and object, knower and known, can’t be as readily distinguished as scientific practice and everyday self-understanding have commonly imagined. By the mid-twentieth century these aspects of indeterminacy allowed this concept to attain some popular appeal. In music, for example, composers like John Cage would speak of musical works that are ‘indeterminate in respect to performance’, and groups like Fluxus would put indeterminacy to work in breaking down all distinction between art and life.

Yet by the 1990s the theorist N. Katherine Hayles, writing on the posthuman, had picked up on another aspect of indeterminacy. Alongside indeterminacy’s emancipatory challenge to seemingly any and all received positions, it had also become associated with an unprecedented restriction of freedom. The features of indeterminacy—liminality, uncertainty, unpredictability—are now accommodated into technologies that manage and monitor behaviour and difference. Where change is permanent, it can seem like there is no change at all. In this context, what was once ‘the human’ is put at risk of becoming no more than a set of points in an agentless circulation of information. The open-endedness of posthuman indeterminacy makes the human available to new forms of regulation and control.

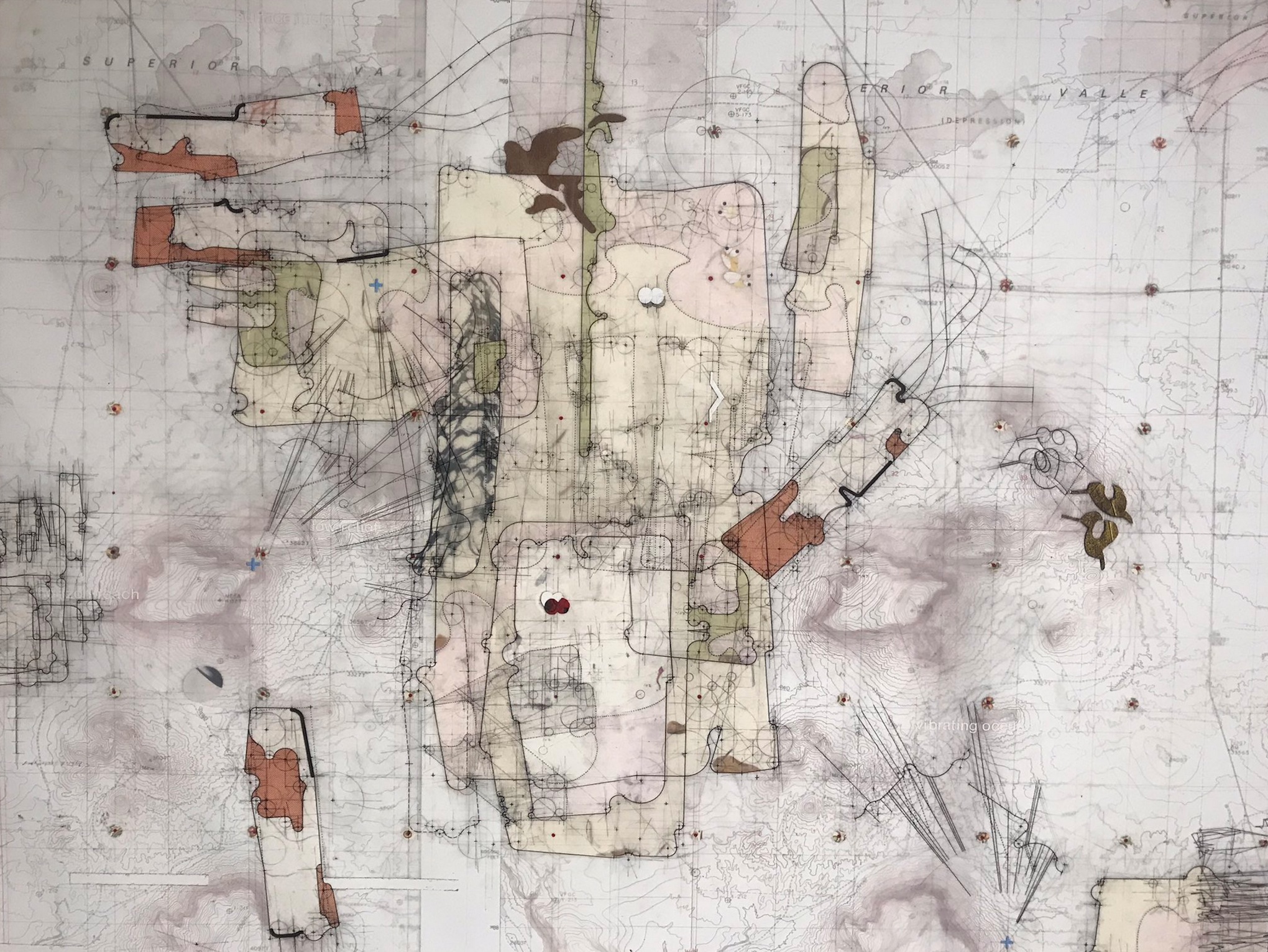

This is the position we find ourselves in. The promise of a liberatory posthumanism has become a new mechanism of governance. As thinking individuals, scholars and practitioners in diverse fields, we must revisit the terms of indeterminacy with the aim of figuring how it functions culturally today. Can anything of what made indeterminacy compelling to the artists and thinkers of the mid-twentieth century be recovered? In the face of seemingly endless streams of information, does it even make sense to talk about navigating or managing our indeterminate present? What’s left of critical agency when our political horizon is shaped by fully automated processes? To find out we have to enact a transdisciplinary enquiry that is not ‘technocratic’, where information circulates between disciplines in the service of predefined problems. We must rather bring together the resources of art practice and theory, philosophy, anthropology, computer science, and more, each with their own distinct approaches to indeterminacy. This way, between us, we can begin to define the problem of indeterminacy anew.

– Iain Campbell

![UKRI AHR Council Logo Horiz RGB[W]](https://indeterminacy.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/UKRI_AHR_Council-Logo_Horiz-RGBW-300x76.png)