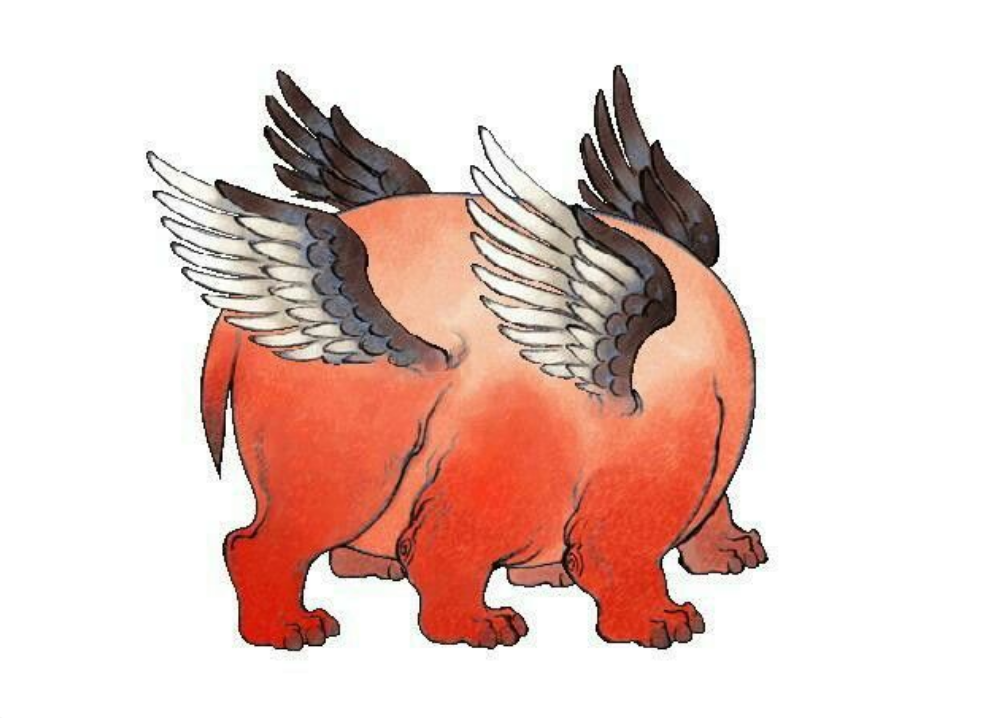

In the Asian tradition, there is a concept-practice called hundun, named after the protagonist of the 4rd century BCE Zhuangzi (and later the 3rd century Daodejing) parable about the emperors Hundun, Shu, and Hu. The emperor of the South Sea, Shu (Quick), and the emperor of the North Sea, Hu (Sudden), often visited the central territory, which belonged to the emperor Hundun (Unformed; Undifferentiated; Chaos). Hundun always treated them very well and Shu and Hu wanted to repay him for his kindness. They reasoned that as all human beings had seven orifices to see, hear, taste, and breathe, and Hundun had none – he was unformed and his back was exactly the same as his front – they would drill an orifice in him every day. They set to work and drilled for six days until, on the seventh day, Hundun died.

In this parable, Hundun’s undifferentiated-ness stands for an openness, hospitality, and nascent creativity that can’t be improved on but is often destroyed by attempts to create order. Inevitably, in all spheres of life, potentiality dies once the determinative choices have been made. Yet, Hundun’s undifferentiated-ness is not bland (as the above image may suggest). It’s a dynamic flow of iterative differentiations, evident in the rhyming repetition of word’s first syllable – hun-dun – similar to the English ‘hodgepodge’, ‘rolypoly’ or Humpty-Dumpty. In Daodejing, the theme of indeterminacy is elaborated by way of ambiguity:

The way is empty, yet when used, there is something that does not make it full.

Blunt the sharpness

Untangle the knots

Soften the glare

Follow along old wheel tracks

Darkly visible, it only seems as if it were there.

Potentiality is here depicted as a dynamic force that can be harnessed but not coerced. ‘Old wheel tracks’ refer to cultivated habit, which guides one’s actions along well-trodden paths. Yet ambiguity is to be valued, too. In its present use, hundun is an adjective, rather than a noun. It designates anything with the characteristic of whirling or turbulence and is seen as creative and positive, rather than threatening or negative. The embrace of this unstable aspect in daily life can be seen in the way Mandarin speakers often contextualise written characters in spoken form, which, in English, would be the equivalent of:

A: Please send this parcel to John Smith.

B: ‘John’ as in ‘John Donne’?

A: Yes, and ‘Smith’ as in ‘blacksmith’. Address: 1 Isle City Street.

B: ‘Ail’ as in ‘church aisle’?

A: No, ‘Isle’ as in ‘Isle of Wight’.

B: ‘Ail of white’ as in ‘White House’?

A: No, ‘Wight’ as in ‘Isle of Wight’, the place name.

B: Oh, ‘isle’ as in ‘island’…

Contextualising a single syllable can be a lengthy affair full of surprising detours. What’s interesting is the implicit acceptance of the indeterminacy of text and context, signal and noise, and communication more broadly. Although practices like these are not applicable to societal-level problems I mentioned in the previous blog, hun-dun-ing in everyday life affords an enlightening experience of instability as turbulence or variability, rather than threat.

– Natasha Lushetich

![UKRI AHR Council Logo Horiz RGB[W]](https://indeterminacy.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/UKRI_AHR_Council-Logo_Horiz-RGBW-300x76.png)